Treatment and Testing for Hepatitis B

Treatment for Hepatitis B

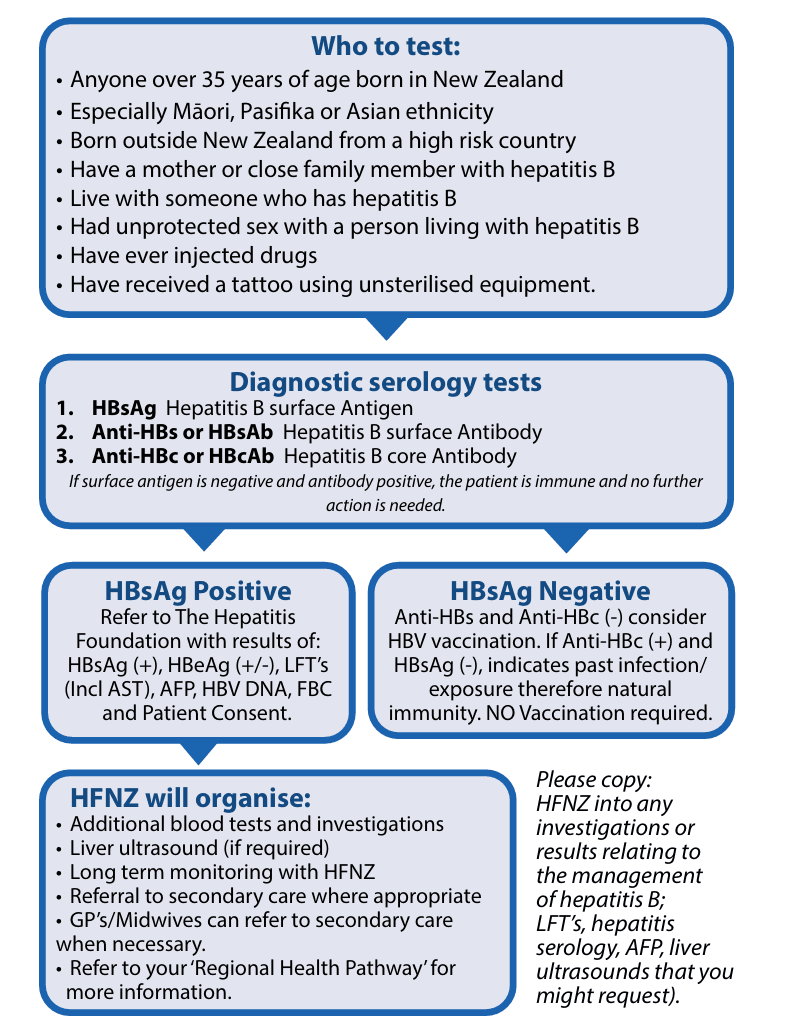

Screening tests for hepatitis B

HBsAg tests whether someone is currently infected with HBV

Anti-HBc indicates current/past infection

Anti-HBs indicates immunity >10 and HBsAg is negative.

HBeAg indicates a high level of infectivity

Initially a positive HBsAg test simply reveals the presence of HBV in the blood. In order to consider an individual to have CHB, a further confirmatory test six months later is required.

HBsAg, Anti-HBs and Anti-HBc testing should be offered to household and sexual contacts of people with HBV and vaccination should be offered via GP to those who are susceptible to the virus. This is free of charge on the immunisation schedule to people under 18, sexual partners, household contacts, and other groups.

All infants of HBsAg positive mothers should have HBIG and hepatitis B vaccine at birth (within 12hrs is recommended). Then Dtap-IPV hepatitis B/HIB at six weeks, three and five months and tested for immunity at nine months.

Refer to the Immunisation Handbook.

Monitoring tests for hepatitis B

HBsAg hepatitis B surface antigen

HBeAg hepatitis B e antigen

LFT Liver function tests (All LFT’s including AST)

AFP alpha-fetoprotein tests

FBC Full Blood Count

HBV DNA Hepatitis B Viral Load (when required)

Treatment for hepatitis B

Dr Chris Moyes, Medical Director HFNZ

Hepatitis B Virus is endemic in New Zealand and many parts of the world including the Pacific, South-East Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. Although universal vaccination of infants has been the policy in New Zealand for over 35 years, there is still a substantial reservoir of chronic infection in older adults and in immigrants of all ages from many countries. In some cases, HBV infection is aggravated by hepatitis D (delta), which is prevalent in Samoa and Kiribati, some other Pacific Islands, parts of Asia and Africa and only found in people with HBV. Consequently, the complications of active hepatitis, cirrhosis, and HCC continues to increase.

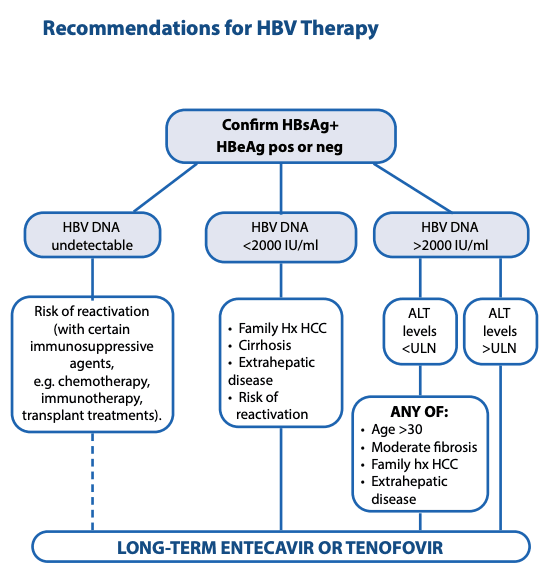

Who should be treated?

Recent updates of guidelines and WHO recommendations have considerably increased the criteria for treatment. Anti-viral medication should be offered to all patients with high viral load HBeAg positive or HBVDNA > 2000 IU/mL with:-

ACTIVE liver disease (ALT raised)

Established liver disease – Fibrosis or Cirrhosis (can be screened for with FIB-4/APRI or fibroscan in non-obese)

• Other major risk factors eg co-infection, diabetes, family history of HCC, or risk of HCC within 10 yrs exceeding 2% (use REACH-B score on MDCalc App see Useful links) – this includes many patients with normal ALT

BPAC also recommends offering treatment to ALL patients over 30 yrs with raised viral load > 2000 IU/mL to reduce integration of viral sequences into host DNA to reduce long-term risk of HCC

Treatment is still not recommended for immune tolerant patients under 30 yrs with very high HBVDNA and normal ALT unless there are other risk factors as above.

Only patients at high risk of HCC, or with established liver disease or co-morbidities need secondary referral – other cases can be managed in primary care.

How long should treatment last?

All patients with chronic HBV once commenced on Anti-Viral treatment until HBsAg negative (often life-long), unless otherwise advised and further assessed under a Specialist.

Chronic HBV patients may need regular lifelong monitoring for any possible hepatocellular carcinoma and/or progression to cirrhosis despite losing HBsAg.

Seroconversion of hepatitis B surface antigen

HBsAg seroconversion when a patient has cleared the Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) from their blood. (HBsAg is negative or not detected).

About one percent of people with hepatitis B will spontaneously lose HBsAg per year. Following seroconversion from HBsAg + to HBsAg - the HBV infection is usually no longer active and they are immune from further infection, but can still be at risk of HCC.

HBV reactivation can occur with potent immunosuppressive therapy and may need cover with prophylactic antiviral treatment.

People who seroconvert >50 years old may still be at risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), although this risk is reduced compared to being HBsAg positive. The Hepatitis Foundation will monitor these people indefinitely.

Patients with close family history for HCC and/or cirrhosis will require 6 monthly liver ultrasound scans in addition to these 6 monthly bloods indefinitely. Cirrhotic Patients should be monitored under Secondary Care Gastroenterology indefinitely and be registered with HFNZ.

Anti-viral Medications

Recommended medications for most patients in NZ are either Entecavir 0.5mg daily or Tenofovir Disoproxil 245mg daily, both of which can be prescribed by General practitioners.

Entecavir is an oral tablet used in adults who have active virus and liver damage. Entecavir is funded as a first-line therapy for patients with chronic hepatitis B.

Almost all patients achieve viral suppression (undetectable HBV DNA) and biochemical response (ALT below the upper limit of normal). Entecavir resistance is rare at less than one percent after six years.

Tenofovir is an oral tablet and is considered to be safest for pregnancy and is the preferred treatment during pregnancy/ breastfeeding and dramatically reduces the risk of vertical transmission. Tenofovir is the first choice for women of reproductive age.

Note: Tenofovir can aggravate renal failure and very occasionally causes renal tubular problems so creatinine, calcium, and phosphorus levels should be monitored, along with periodic liver function and viral load (HBV DNA quantification). Patients with renal impairment should be prescribed Entecavir rather than Tenofovir and may need a reduction in dose if GfR <50ml/min.

No resistance to Tenofovir has been observed after five years of therapy. Renal function (creatinine, calcium, and phosphorus) should be assessed before commencement of Tenofovir and periodically while on treatment.

Both are extremely effective at suppressing HBV and reduce liver damage and HCC risk with very few side effects and no interaction with other medications, but need to be continued long-term.