No-one knew what it was. A new type of hepatitis linked to drug use and blood transfusions. Best case scenario, they would stay alive long enough to make it to Australia for a transplant. Even then, about a quarter would get the disease in the new liver and die within a few years.

That was the 1980s, when Ed Gane was a newly minted registrar in Auckland. Most liver failure patients had hepatitis B, which was mostly contracted in childhood and for which there was no cure. But Gane's mentor, Cliff Tasman-Jones, wanted him to see this new disease, so he took him to Auckland's rehab units.

So began an extraordinary career that has traced the arc of a disease from diagnosis to cure, leading game-changing global drug trials and helping set up New Zealand's liver transplant programme along the way.

In 1989, they gave the new disease a name – hepatitis C. It wasn't really new – they think it had existed for about 40 years. But the Mr Asia-fuelled heroin boom of the 70s and 80s speeded its spread. Young people trying drugs for the first time inevitably shared needles. You only needed to use once.

And as those experimenting youngsters aged, they arrived in hospital with cirrhosis or scarring of the liver, or liver failure, or liver cancer.

Determined to help halt their certain march to death, Gane travelled to King's College, London, where he trawled back through 1000 recent transplant patients to see how many had hepatitis C.

The results were astonishing, given some of his colleagues had warned him off studying hepatitis C as they didn't believe it caused severe disease. And anyway, it was self-inflicted, they said. But Gane's research showed hepatitis C was the most common reason people needed liver transplants.

"It became clear to us that the sleeping dragon was the epidemic of hepatitis C."

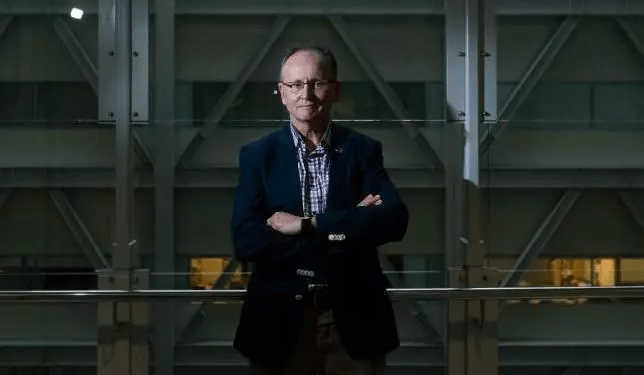

For 90 minutes, Gane barely draws breath. You get the feeling he lives to talk livers. His manner is more GP than brusque specialist – he speaks gently, without jargon or condescension.

He plays down his role in the development of a cure. He was lucky, he says. Lucky to work with global drug companies that trusted him to run the first treatment trials. Lucky to work with such great colleagues who allowed him time for clinical research, in addition to his job as deputy director and chief physician of the Liver Transplant Unit.

Lucky to have such amazing chemists who designed the drugs, and the patients who bravely volunteered to try them. Not to mention his wife Penny, a pathologist, who is brilliant and has always supported him.

He talks in colleague and transplant surgeon Stephen Munn's office. It's bigger than his, which is next door. Surgeons get all the glory. He didn't say that, obviously.

Gane, Munn, intensive care specialist Stephen Streat and surgeons Phil Bagshaw and Bryan Parry finally set up New Zealand's first liver transplant unit in 1998.

By then they had a new treatment to curb hepatitis B, but the only option for hepatitis C – interferon – was so toxic that patients preferred to deal with the disease. For six months or a year, they'd have three injections a week that would make them feel as if they had the flu. Chills frontman Martin Phillipps later called it more chemotherapy than cure.

"Not only do they feel as if they have the flu, they can get depressed, they lose weight, they can even be suicidal," Gane says. "Many of them have to stop work. So they put up with a year of really bad health and bad side-effects and, at the end of that year, only between 10 and 20 per cent were cured. And word got out, so people didn't want to come forward for treatment."

While at King's, Gane had worked with drug company Roche as principal trial investigator for a drug targeting a post-transplant viral infection. That gave him profile, which he believes is the biggest barrier to establishing more early phase clinical trials in New Zealand.

In about 2006, Roche asked if he wanted to trial their new hepatitis C drug, in combination with another drug. For the first time, they showed you could make hepatitis C undetectable in the blood. The results were published in prestigious journal The Lancet and Gane presented them at international conferences. More profile, more trial offers.

In 2010 he ran trials for sofosbuvir. Twelve weeks of treatment, all 40 patients cured. After he presented those game-changing results, in 2011, he made the Financial Times. "Unshowy", it called him. That's an understatement.

"My reaction was 'Wow, that is great', because at the same time, we were seeing more and more people coming to us for transplant, because that big population of people with hepatitis C – those 50,000 people – were getting older and older".

All up, Gane's trials treated about 3000 Kiwis. Plucked them off the "brink-of-death" transplant list. Some already had irreversible complications. The rest were suddenly cured. After treatment rates of about 100 a year with interferon, the numbers were a revelation.

"Not often in medicine you get to see people, cure them and they feel better. It's incredibly gratifying to see that in front of your eyes."

But then the drugs went from trials to market.

"You've probably heard about exorbitant pricing. So we weren't able to use these drugs. That to me was a real shock."

Priced about $100,000 per treatment course, they were out of reach of most patients. Some used buyers' club groups to access cheap imports. But even that came at a cost too great for some.

Gane won't comment on drug company pricing, but has only praise for Pharmac's speed of funding them. Even at the cost of $1000 a pill, cost, the drugs were a financial no-brainer – a short-course cure that can prevent the cost of a lost life or a $150,000 liver transplant.

In February, Pharmac funded Maviret, which is so effective Gane calls it the end of the line for hepatitis C treatment.

So has he done himself out of a job? "I hope to do so, but not for the next few years. My kids are still young." He has three daughters, aged 13-18. None wants to do medicine.

Now he has a new problem.

With Maviret, they're treating a "phenomenal" 500 people a month. At that rate, they'll eliminate hepatitis C well before the World Health Organisation's 2030 goal. Except they won't, because 40-50 per cent of hepatitis C sufferers don't know they have the disease.

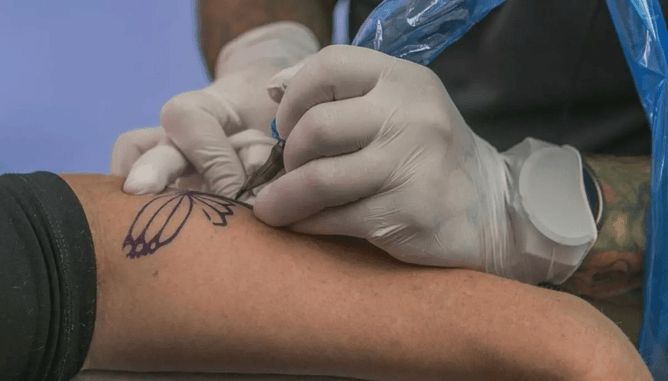

About 1000 new cases are diagnosed each year. Some are new transmissions – prisoners spreading it through illicit tattoos, needle-sharing drug users. But many are still the long tail of drug experimentation.

Gane is working with the Health Ministry to devise an action plan to get people tested and treated. Now there's an easy cure for every type of the disease, there's no excuse, he reasons.

"You are talking about people who may have experimented with drugs in their teens, who are now doing everything. They've gone through uni, they are pillars of the community, they're working as professionals, as doctors, lawyers, accountants. They're working as tradespeople. They're everyone. But they don't know that they have it."

Story published on www.stuff.co.nz on July 6, 2019.